Read the full story

Foundation brings unique insights on business, building product, driving growth, and accelerating your career — from CEOs, founders and insiders.

The Power Law: How to Pick An Investor

Don't set up a business to fail 9 times out of 10.

In the card game of Hearts, your goal is to accumulate the fewest number of points each round. Each heart-suited card is worth 1 point and the queen of spades 13 points, for a total of 26 possible points. Players try to finish each round with as few points cards as possible.

But there's another way to win a round: shooting the moon, when you do the opposite of what you would normally do, collecting all cards worth points. When you accumulate all hearts cards and the queen of spades, you finish a round with zero points and cause your opponents to take 26 points each instead. If you miss by just one card though, you will probably lose the entire game.

The power law

Great fortunes have been won and lost by trying to shoot the moon.

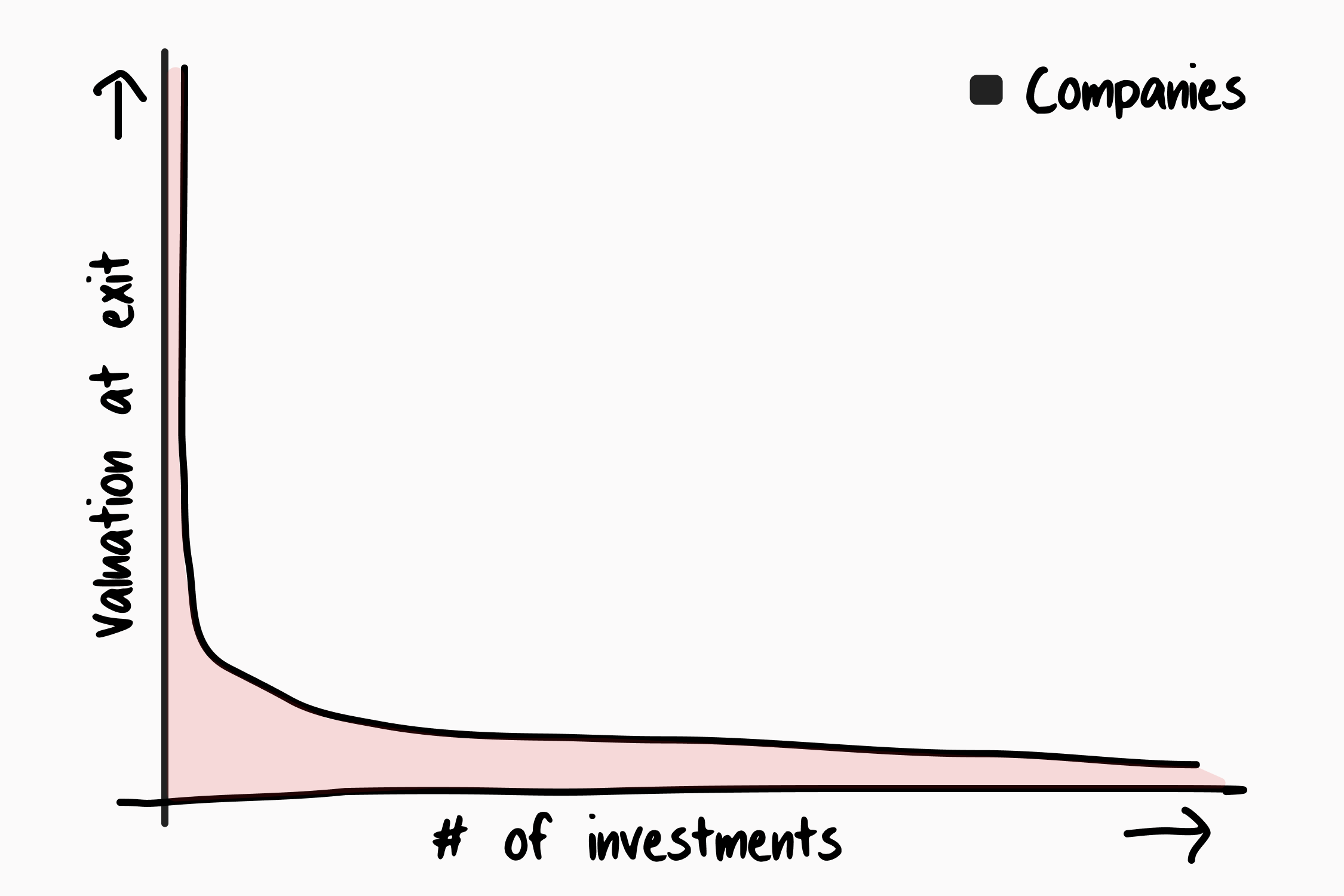

In venture capital investing, there is a "power law" concept: that a single investment can return orders of magnitude more than all other investments in a portfolio combined.

In my experience as a founder who has raised over $200 million and pitched hundreds of investment firms over the last decade, I have met two types of investors:

- Investors who try to shoot the moon

- Investors who don't try to shoot the moon

I have met smart investors who use each strategy, and investors can make money using either strategy.

But this math is very different for founders and employees, which we'll show below.

Shoot the moon?

Founder beware of cheap capital that pushes growth at all costs.

Investors who try to shoot the moon build a portfolio of extreme bets. Growth at all costs. Even once a company reaches hundreds of millions of dollars in revenue, it should try everything possible to reach 200% annual growth, business fundamentals notwithstanding.

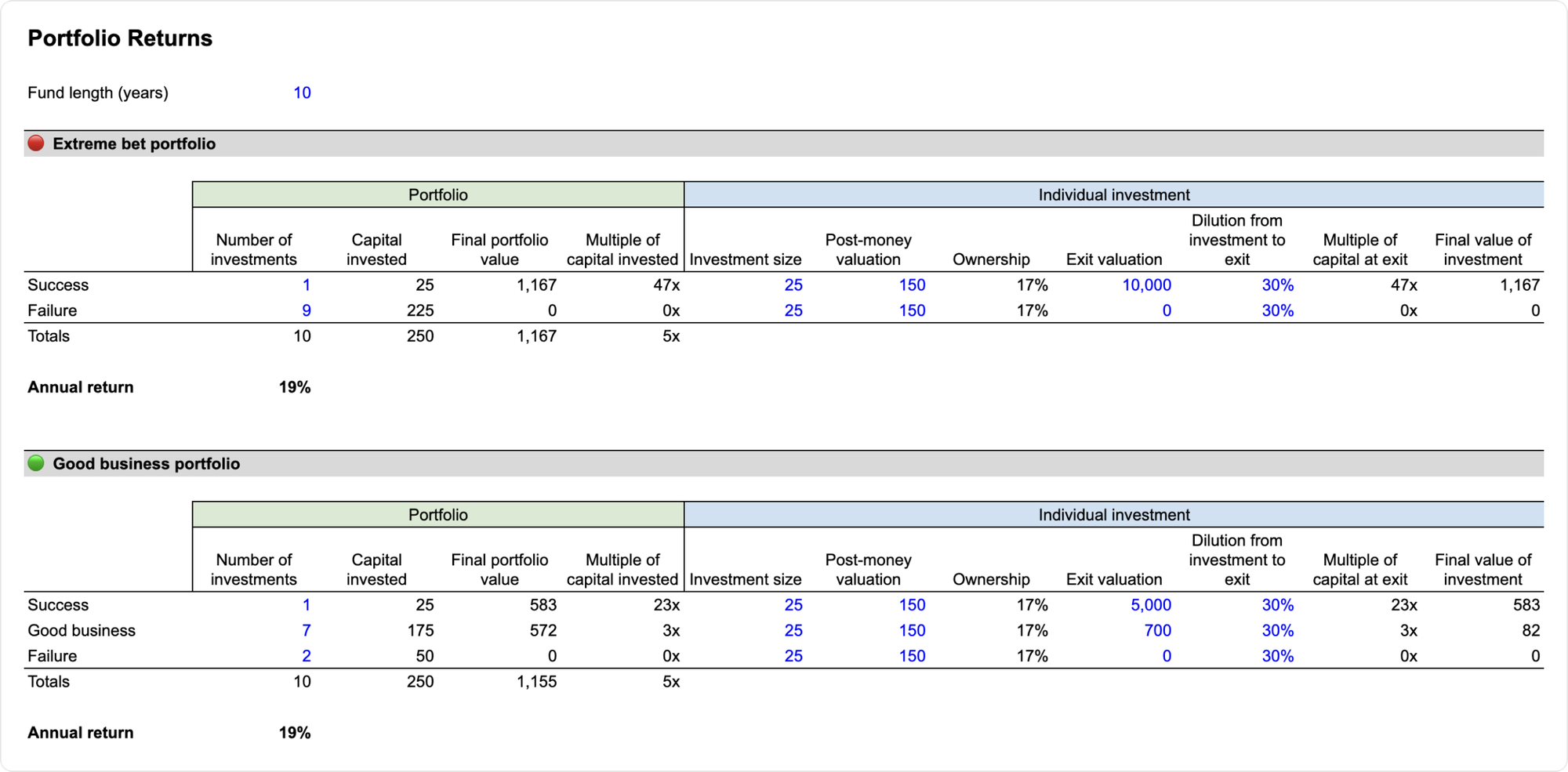

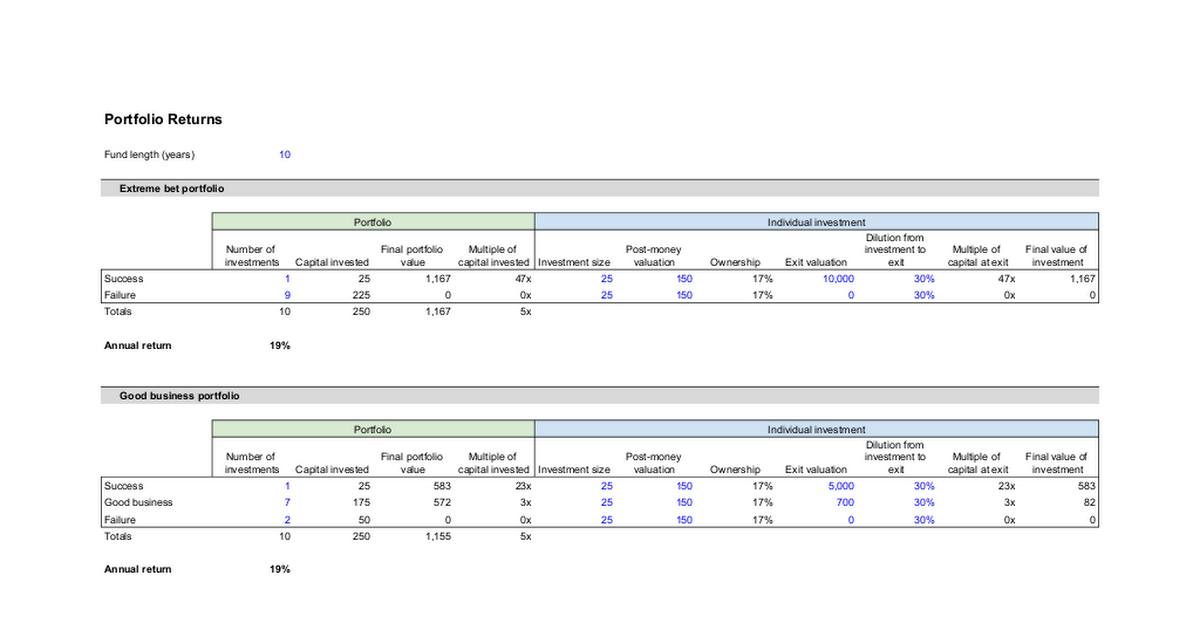

This strategy can work for an investor if every company in a portfolio follows it, and if the investor has a knack for finding asymmetric bets with great upside. For a fund investing at the Series B stage (at approximately $150 million valuation), the portfolio succeeds if 1 in 10 bets is extremely successful, even if the other 9 bets return nothing in total.

See the portfolio returns spreadsheet for the math behind the strategy: one company worth $10B makes up for 9 companies worth nothing.

This strategy has two problems:

- Valuation multiples must keep growing. 1 out of 10 investments has to return 50x after dilution, which is likely a $10B exit. Succeeding at this level so frequently requires near clairvoyance, unless subsequent investors are willing to pay increasingly higher valuation multiples, artificially inflating company worth. This is what happened in the zero-interest-rate period.

- Investor and company are not aligned. In the Extreme Bet portfolio above, 9 out of 10 companies—founders, executives, employees—get nothing. How can a leader run a business structurally likely to fail 9 out of 10 times? Companies take a decade to build, usually during the team's prime decade in life.

A disciplined portfolio

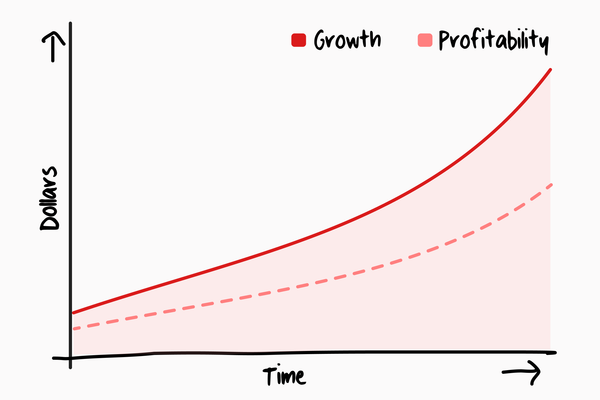

A better model looks like the Good Business portfolio model above. The best company in the portfolio reaches a $5B valuation (a great feat, but not rare in the public markets), the majority of companies build solid, profitable businesses, and only a couple fail.

Both the Extreme Bet and Good Business portfolios return almost 20% per year. In the first portfolio, 10% of founders and employees make money and the rest lose everything; in the second, 80% make money.

Critical to the Good Business portfolio is the realization that you must first build a solid business before building a wildly successful one. Skipping to wild success is like trying to shoot the moon. It's a bad idea to maximize your chances of being the next TikTok, while ignoring business fundamentals. A single misstep can destroy a decade of effort, leaving hundreds of employees with nothing.

Picking an investor

Strive to build a generational business with partners who value both good businesses and great businesses.

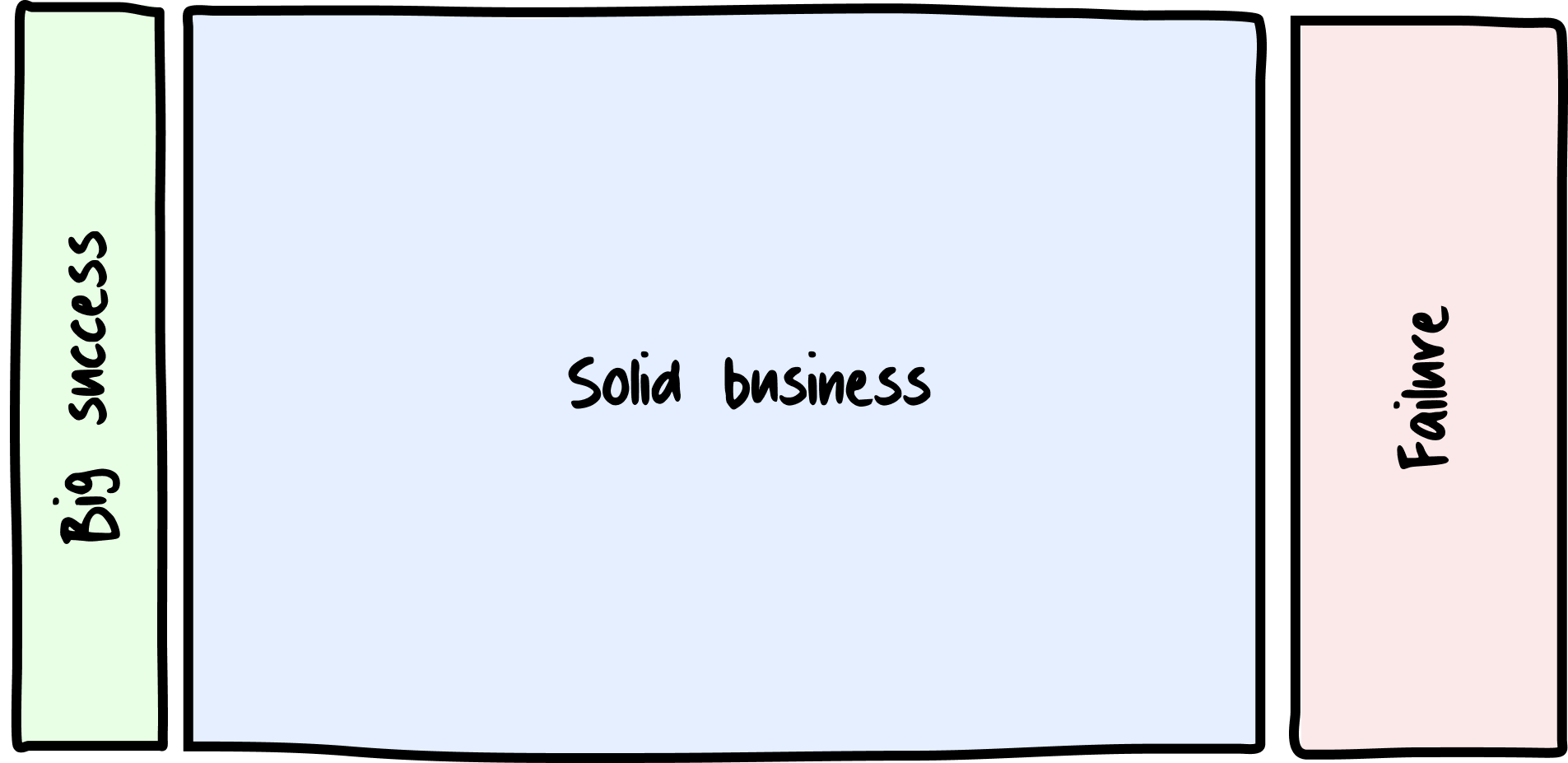

There are three discrete outcomes to venture capital backed companies:

- Big success

- Solid business

- Failure

When raising capital, find an investor who is comfortable with both outcomes 1 and 2 above.

Below are guidelines, learned over a decade of fundraising, for picking an investor:

Read the full story

Foundation brings unique insights on business, building product, driving growth, and accelerating your career — from CEOs, founders and insiders.